What causes bus bunching in NYC and how can we combat it?

Written by Laura Greenstreet

What causes bus bunching in NYC and how can we combat it?

New York City buses carry over 2 million riders each day, more than twice as many as any other US city. For many riders, buses are the main way to reach important destinations like work, school, and medical appointments. However, New York City buses are often slow, late, and unreliable.

For my Siegel PiTech PhD Impact Fellowship, I partnered with Riders Alliance, a grassroots organization that advocates for transit that meets the needs of all New Yorkers. Riders Alliance was interested in how optimizations to the bus schedule could reduce “bus bunching” and improve reliability.

Unreliable buses change how riders use the transit system. Even if a rider’s bus is only seriously delayed one day a week, they might leave home 30 minutes earlier every day to ensure they make it to work on time. An extreme form of unreliability is called “bunching”, which happens when two or more buses travel within 25% of their scheduled headway. On frequent routes, this often means multiple buses travelling together, leading to crowded buses and long wait times.

What is “bus bunching”?

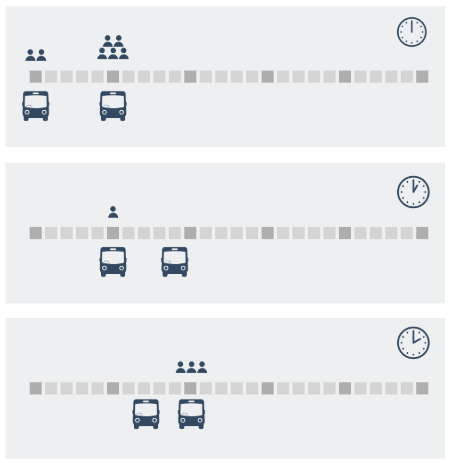

Deviations from the schedule are exacerbated by positive feedback cycles that lead to bunching. Here, the first bus takes longer than expected at the first stop due to a large number of passengers. This leads to fewer passengers for the next bus and more for the first bus, driving the buses closer together.

Why do buses bunch?

Bus bunching isn’t a new problem - it has been studied since the 1970s with many anti-bunching strategies proposed. Bus bunching is driven by positive feedback cycles, where a bus that is delayed will have more passengers to pick up at any given stop. The bus that directly follows it will in turn run ahead of schedule, because it will have fewer passengers to pick up. The cycle forms as the buses are driven closer together, as the first bus keeps picking up more passengers and falling further behind, while the second bus keeps making fewer shorter stops and running ahead. Anti-bunching strategies try to avoid bunching by making loading or travel times more consistent or by breaking feedback cycles, for example, by having buses wait if they are too close to adjacent buses.

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) has tested a variety of strategies on at least a few routes in NYC, often with mixed or negligible results. Previous work often focused on a single strategy, but the mixed results motivate a different one: first create a framework to understand what drives bunching on each route and then compare mitigation strategies. For example, on one route bunching might be caused by a traffic light that introduces variability that could be reduced by a bus priority signal. On another route, bunching might be driven by high ridership variability near universities and schools, so staggering bus departure times to account for ridership spikes could help.

Simulation Framework

To understand the causes of bunching and compare mitigation strategies, we developed a simulation framework using millions of daily bus observations scraped from the MTA BusTime API by the Bus Observatory project.

The simulation provides a powerful framework to change parts of the system to understand causes and compare anti-bunching strategies. For example, we were surprised to find that eliminating secondary delays, or delays at the start of a route from a bus finishing its last route late, resulted in much larger impacts than reducing travel time variability between stops. For many routes, eliminating secondary delays halved bunching, though for some it had little impact, highlighting the importance of choosing strategies based on the route.

Our other key findings were about how the system impacts riders. Holding strategies are a popular class of anti-bunching strategies where a bus waits at some stops based on a rule. For example, most cities use timepoints where a bus waits until its scheduled time if it arrives early. More complex holding strategies use GPS data so each bus can space itself out between the next and previous bus. While we found holding strategies reduced bunching and rider wait times, they consistently resulted in longer rider travel times, as riders spent more time waiting on the bus than they saved from more evenly spaced buses.

We also found that increasing bus lateness alone generally didn’t make more riders late. As an extreme example, notice that if all buses on a route that ran every 10 minutes were 10 minutes late, all but the first riders would arrive on time. While the situation is generally not that extreme, this result is another instance where improving bus metrics doesn’t improve rider experience. While bus-level metrics are easier to measure and optimize, our results suggest it's important to measure and optimize for rider metrics to ensure benefits to users.

Impact & Path Forward

Laura Greenstreet

Ph.D. Student, Computer Science, Cornell University

The initial simulations helped us understand route-level causes of bunching and that improving rider metrics is more important than reducing bunching alone. I’m continuing the collaboration with Riders Alliance into the fall of 2025, developing an optimization framework to test the potential for holding strategies focused on rider metrics. We’re also excited to explore the potential for synergies between multiple strategies.

I’m grateful to PiTech and Riders Alliance for the opportunity to work on this project. It aligns closely with my research interests on data-driven systems, optimization, and predictive modeling. It has also been exciting to learn about New York City’s transportation system. I’m excited that our findings can inform practical ways to improve bus service for New Yorkers by making smarter use of existing resources.